The purpose of the Balboa Park Cultural District is to illustrate and celebrate

the progress, possibility, and interconnectedness of the world and the human race.

A Conceptual and Geographic Area

In order to succeed as a Cultural District, it is important that everyone who influences the outcomes set forth in this plan build from a common base of knowledge. The more we collectively understand the histories and contexts that influence people’s experiences in the Cultural District, the more successful we will be in moving the Cultural District forward, together.

The following section outlines the Cultural District’s origins, histories, legacies and systems that influence its ecosystem today, developed from stakeholder, thought partner, and advisory board inputs, as well as interviews with community members who visit the Cultural District.

Balboa Park Cultural District is state-designated

The California Arts Council’s cultural districts program aims to assist Californians in leveraging the state’s considerable assets in the areas of culture, creativity, and diversity. A cultural district is generally understood as a well-defined geographic area with a high concentration of cultural resources and activities.

California Cultural Districts highlight the cultural legacy of our state’s most valuable resource—its diversity. From larger, urban areas to uncharted rural locations, each district helps grow and sustain authentic arts and culture opportunities, increase the visibility of local artists, and promote socio-economic and ethnic diversity through culture and creative expression. 14 districts will serve as California’s inaugural state-designated Cultural Districts, highlighting some of the thriving cultural diversity and unique artistic identities within local communities across California.

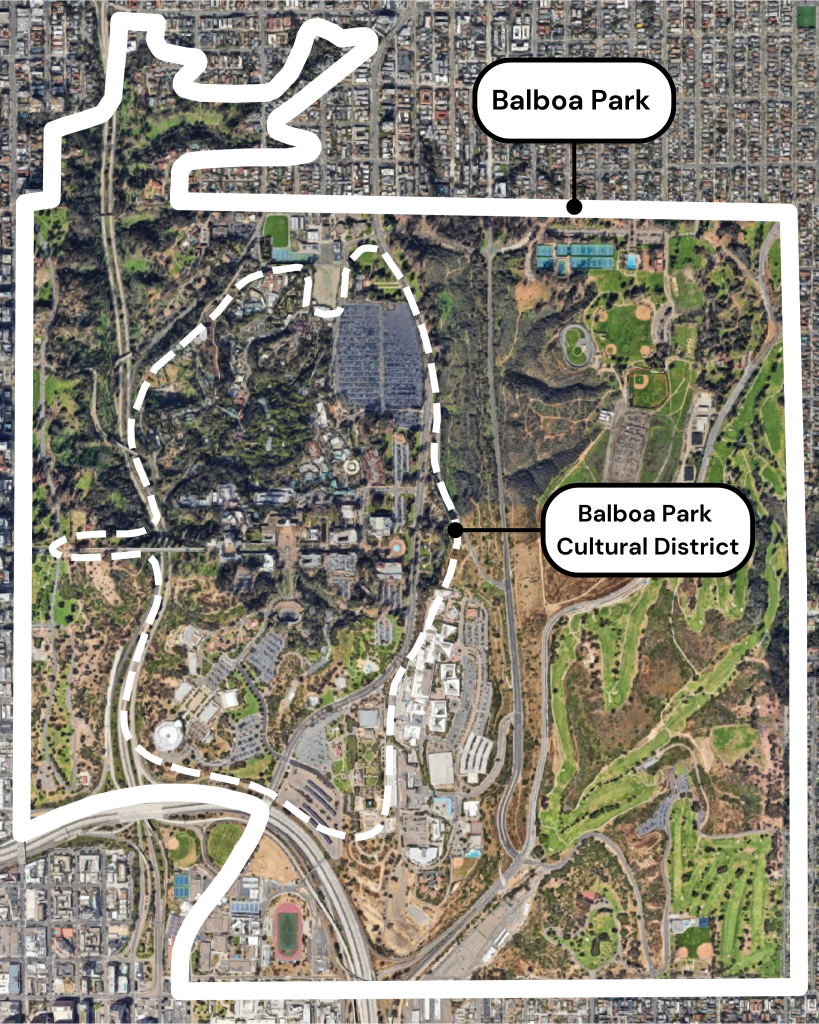

The Cultural District is part of and distinct from its regional park.

The Cultural District is an approximately 400-acre area nestled within Balboa Park, a 1,200-acre city and regional park sitting on unceded Kumeyaay land in San Diego, California, and one of the most visited attractions in Southern California by people in and outside of the state. On average, over 230,000 people experience the Cultural District each week, adding up to nearly 12 million visitors annually (based on 2019 combined attendance reporting and other surveys and reports). The District serves an important role as an educational space, serving thousands of students every year between field trips, after-school and camp programs, and youth arts classes. It also showcases many community groups, activities, and contemporary artists, displaying the work of 236 artists in 36 working studios.

The Cultural District is currently managed, maintained, and governed by multiple layers of public, nonprofit, and private systems, policies, regulations, and processes that make for a particularly complex governance ecosystem compared to the typical city park, as well as other California state-designated cultural districts. It’s also a historic site, with the 1915 and expanded 1935 sites registered as a National Historic Landmark and a National Historic Landmark District, and many of its buildings placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Cultural District is designed to be a global stage for culture.

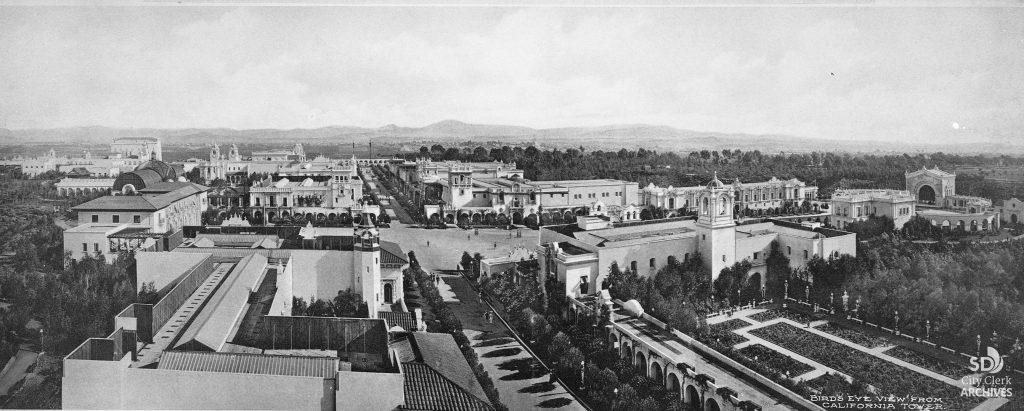

From the beginning, the Cultural District had big ambitions with a very distinct purpose. San Diego business and community leaders recognized the great potential to attract a new wave of European visitors coming through the newly-opened Panama Canal, and saw this as an opportunity to showcase San Diego for a global audience. The creation of the 1915 Panama-California Exposition gave the visitors a reason to stop in a town of fewer than 40,000 residents at the time. The president of the Exposition, D.C. Collier, said:

“The purpose of the Panama-California Exposition is to illustrate the progress and possibility of the human race, not for the exposition only, but for a permanent contribution to the world’s progress.”

For the second exposition in 1935, innovation was again on display, this time paired with showcasing cultures of the region and the world in an effort to extend understanding, empathy, and peace. Both expositions were hugely successful, generating millions of visits.

The Cultural District’s original vision is challenged by a legacy of exclusion.

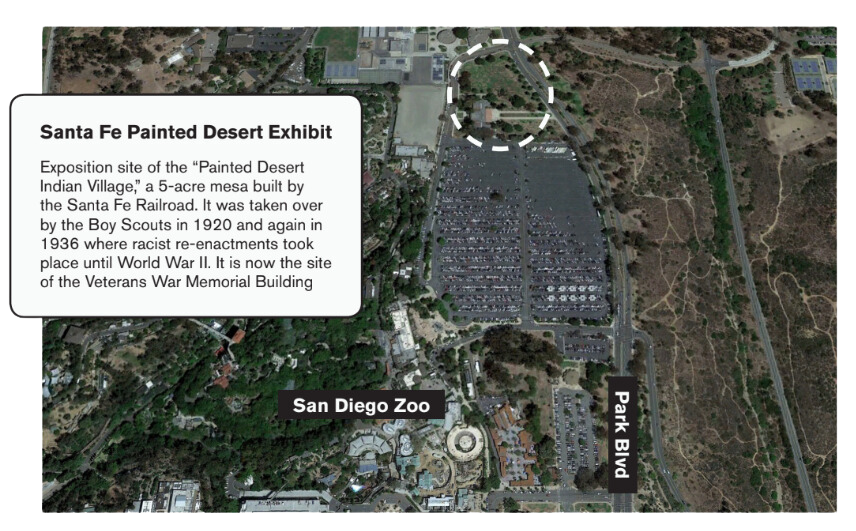

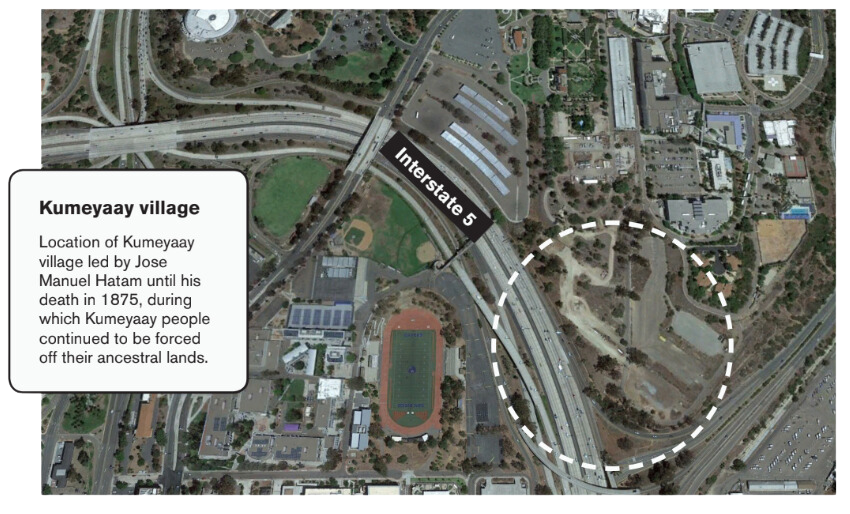

Before the city broke ground for the 1915 Exposition, before Balboa Park (then City Park), and before the city of San Diego, Kumeyaay people were forcibly relocated throughout the region. Then in 1915, the Panama-California Exposition included an “Indian Village” exhibit of Pueblo Indians primarily from New Mexico, not reflective of the city or region’s Indigenous people.

From the expulsion of the region’s Kumeyaay communities to redlining policies across San Diego, Balboa Park’s own century-long history intersects with local policies of exclusion that have prevented many from enjoying all it has to offer.

Over the last 10 years, the region’s population has continued to grow and diversify, with Asian and Hispanic communities as well as senior populations, increasing. The region is a drastically different place from when the Cultural District was established in a city with a population of 39,578. Cultural District leaders, stakeholders, and staff acknowledge that this continues to affect how people experience and perceive the Cultural District today, which for many, is a feeling that this is not a place for them.

Balboa Park’s recorded history of Indigenous spaces